July 1 marks one year since Florida reformed its mandatory minimum sentencing law known as “10-20-Life” by removing aggravated assault with a weapon from the list of crimes subject to the statute. Although it’s still early and the statistical data hasn’t been compiled, the legislation’s first anniversary is a good time to look back at how it all came about, its impact, and what it means for the Florida’s bail bonds industry.

Contents

10-20-Life

The mandatory minimum sentencing law known as 10-20-Life dates back to 1999 and the first Jeb Bush administration. An editorial in the St. Augustine Record applauding the 2016 reform recalls that the law was a major part of the governor’s election platform in the wake of a spike in violent crime and claimed the law served “no good reason other than politics.”

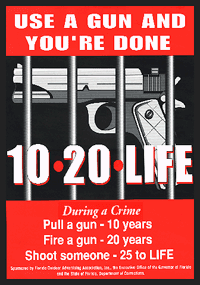

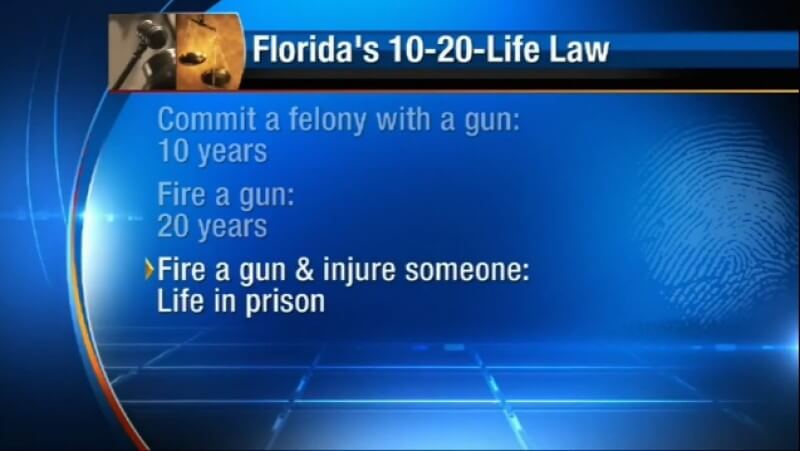

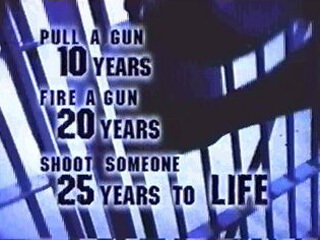

It required a minimum 10-year sentence for anyone who had a firearm on his or her person when committing any one of a number of crimes, including aggravated assault. Firing the weapon meant an automatic 20-year sentence. Hitting someone else meant a minimum sentence of 25 years to life.

It required a minimum 10-year sentence for anyone who had a firearm on his or her person when committing any one of a number of crimes, including aggravated assault. Firing the weapon meant an automatic 20-year sentence. Hitting someone else meant a minimum sentence of 25 years to life.

The Miami Herald notes that the state sentenced more than 15,000 people under the law, a great many of whom were the sort of dangerous people the law originally targeted. However, as the Herald quotes Greg Newburn of Families Against Mandatory Minimums as pointing out, “Unintended consequences are inherent to mandatory minimums. No one anticipated 10-20-Life would be used to put citizens in prison for 20 years for warning shots, but that’s exactly what happened”.

Some of these unintended consequences included high profile cases such as the case of a disabled veteran who fired a warning shot to protect a friend or a young entrepreneur who fired shots into the air to deter a group of men threatening him in a parking lot. These cases and others gave rise to a movement to change the law.

The case of George Zimmerman, who was acquitted of murder but could well have found himself incarcerated under 10-20-Life had Trayvon Martin only been wounded or not hit at all, brought even more attention to the law’s unintended consequences when even a task force appointed by the governor recommended its reform.

In addition to legislators from both sides of the aisle, public defenders, prosecutors, and law enforcement all supported the effort to change the law. CS/SB 228 passed the House and Senate unanimously (119 to 0 and 38 to 0, respectively). Governor Rick Scott signed the bill into law on February 24, 2016, with it taking effect July 1.

10-20-Life and the Bail Bonds Industry

Though not as high profile as some of the cases cited by those who were advocating for reform, the mandatory minimums had unintended consequences for the bail bonds industry as well.

In a profession that involves apprehending and bringing to court people who would rather not go, the law posed a risk to any bond enforcement agent who had to act in self-defense.

In a profession that involves apprehending and bringing to court people who would rather not go, the law posed a risk to any bond enforcement agent who had to act in self-defense.

The risk was not academic: in 2005, a bondsman in Palatka, Florida, found himself sentenced to 25 years after shooting a fugitive whom he was trying to apprehend. The bondsman, Danny Buchanan, claimed that he fired in self-defense when he thought the fugitive, Kevin Brinson, was reaching under the seat of a friend’s car. Not knowing what the three-time convicted felon was reaching for, Buchanan fired and hit Brinson in the buttock.

The jury did not agree that Mr. Buchanan’s actions were in self-defense, nor did they agree that bail bondsmen have any special rights to use force in apprehending a fugitive. Although he had denied a pre-trial motion to dismiss, the judge had stated that he thought the sentence was inappropriate, but that the legislature had tied judges’ hands with the 10-20-Life Law.

Effects of reform

With just less than a year since the reform of 10-20-Life went into force, there is not a great deal of data to weigh its true impact throughout the state. While we can conclude with reasonable certainly that less people are being put away for extended periods, there is as yet no research to quantify that amount.

While the legislature was considering the reform, the professional staff of the Senate’s Committee on Fiscal Policy noted that as of June 30, 2015, 2.3% of the inmates serving time under 10-20-Life with a primary offense of aggravated assault, so the reduction is likely to be relatively small, especially given that the change is not retroactive.

While the legislature was considering the reform, the professional staff of the Senate’s Committee on Fiscal Policy noted that as of June 30, 2015, 2.3% of the inmates serving time under 10-20-Life with a primary offense of aggravated assault, so the reduction is likely to be relatively small, especially given that the change is not retroactive.

Representatives of the Professional Bail Agents of the United States, the National Association of Bail Enforcement Agents, and the Florida Bail Agents Association were contacted for this article, but none of them replied with a comment. It should be clear, however, that the law’s reform makes a difference for their industry, though the type of bail bond does play a role.

If, as the precedent in Danny Buchanan’s case (and the statement from the State Attorney’s office) suggests, bail bondsmen have no more right to use force than a normal citizen, then the 10-20-Life law carried with it an inherent risk of lengthy incarceration as the result of a split-second decision on the job.

Now, however, while a bond agent could still conceivably find him or herself charged with aggravated assault in the course of apprehending a fugitive dead set on avoiding court, the agent who chooses to be armed no longer risks an automatic minimum decade in prison.

Judges are now free to exercise discretion and, well, judgement in weighing the unique circumstances in each case. If Buchanan were standing trial today, the circuit judge – who stated on record that he felt the 25-year sentence was inappropriate – would have the leeway to impose a much smaller sentence.

In a profession where one is rarely working with people who are at their best, the knowledge that a split-second decision won’t necessarily mean risking a quarter century in prison has to be of some comfort.